For millennials, it ain’t looking good, but are hard-hitting campaigns just fat-shaming and counterproductive?

The video features a small white box that looks like a cigarette packet. No pictures, just stark lettering.

People on the street are shown the box and asked a question: “What is the biggest preventable cause of cancer after smoking?”

They guess. Drinking? Sunbeds? No. The packet is opened. It is stuffed with greasy, plump slap chips.

On bleak white posters and billboards splashed across London and the United Kingdom and a barrage of social media messages the question is repeated.

Some letters to the answer are left out, in an easy game of hangman. OB_S__Y.

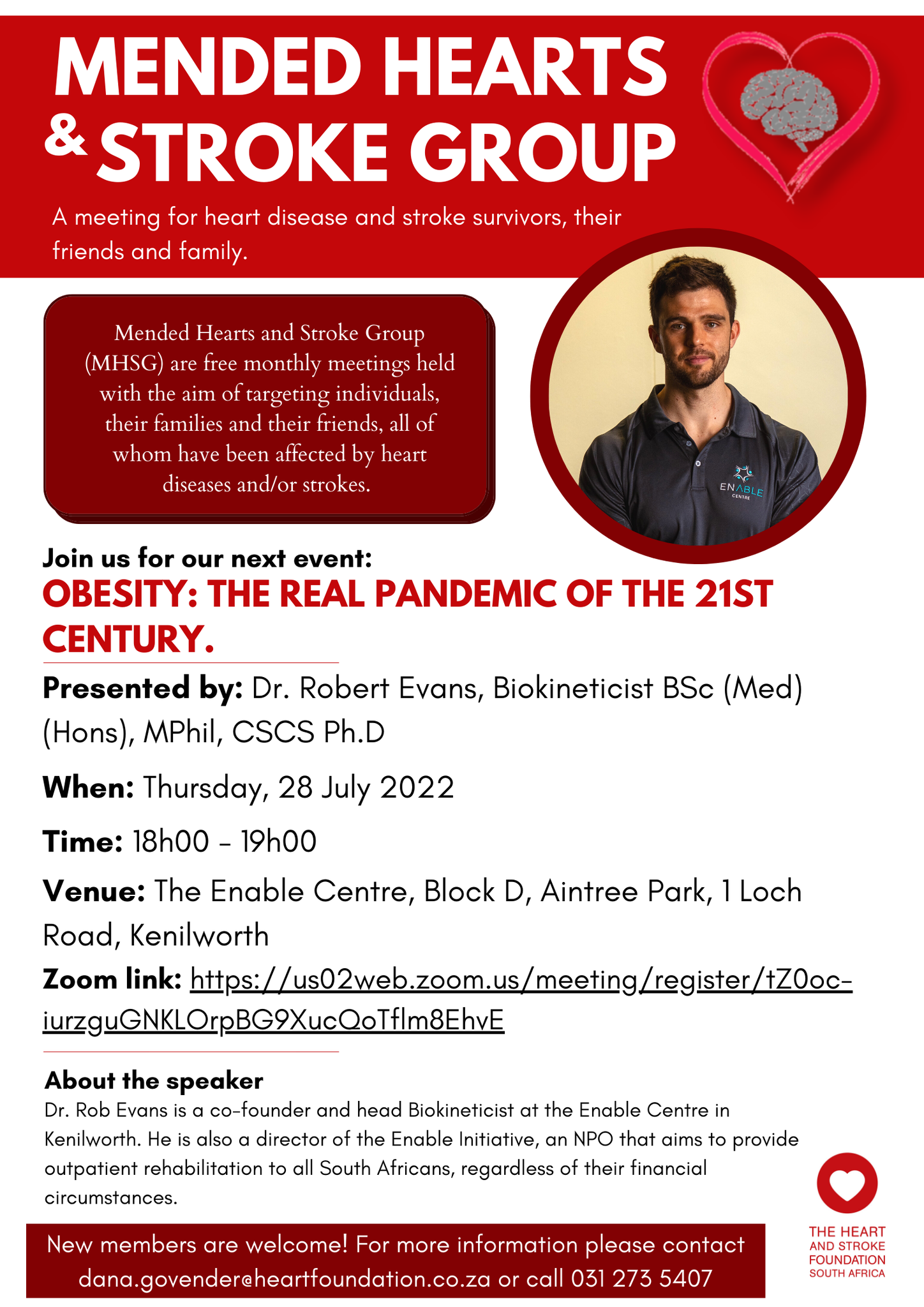

Yes, Cancer Research UK wants to tell the British public in a hard-hitting advertising campaign, being overweight or obese could be the new smoking: as smoking rates fall, obesity levels have crept up. If the trend continues, obesity may eventually overtake smoking as the biggest cause of cancer.

The message is SC_RY.

The country’s millennials — the supposedly quinoa-loving, juicing, detoxing generation born between the early 1980s and the mid-1990s — are likely to be the most overweight since records began, Cancer Research UK calculates, based on Health Survey for Englanddata from 2015.

More than seven in 10 millennials will be overweight by 2026-2028, the organisation predicts. This compares with around half of all baby boomers — those born between 1945-55 — who were overweight or obese at the same age.

In South Africa, obesity figures are equally alarming. South African women have the highest overweight and obesity rate in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a 2014 study published in the medical journal The Lancet.

The country’s 2016 demographic and health national survey reveals that two out of every three women (68.5%) and just over a third of men 15 years and older are overweight or obese. The Lancet study’s results were similar: 69.3% for women and 39% for men.

South African women’s obesity and overweight rate is almost double the global rate of about 30%, according to The Lancet study, for which researchers collected data from 188 countries.

For adults, overweight and obesity ranges are determined using weight and height to calculate a person’s body mass index (BMI), which for most people correlates with the amount of body fat. Overweight is defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 and obesity as a BMI of 30 or more, according to the United States government’s Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

A woman who is 1.65m tall and weighs 69kg, for example, has a BMI of 25.3 and is therefore overweight. If a woman of 1.73m weighs 90kg, her BMI is 30 and she is obese. (There are some exceptions, such as sportspeople.)

“While obesity groups tend to increase in the older age groups, South African millennials are also affected, with three out of five women and one in five men between the ages of 20 and 34 years estimated to be overweight or obese,” says Jessica Byrne, a registered dietician and spokesperson of the Association for Dietetics in South Africa (Adsa), referring to statistics in the 2016 demographic and health survey.

“South Africa faces a massive and growing burden of obesity.”

Lifestyle changes may prevent 4 in 10 cancers

Lifestyle changes may prevent 4 in 10 cancers

Being overweight or obese is linked to 13 different types of cancer, research published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016 shows. This includes cancers of the breast in postmenopausal women, says Lorraine Govender, national advocacy co-ordinator of the Cancer Association of South Africa (Cansa), as well as cancer of the colon and rectum, endometrium, kidney and pancreas. It may also be associated with an increased risk of cancer of the liver, cervix, ovary and aggressive prostate cancer.

Statistics from the South African National Cancer Registry reveal a steady increase in the incidence of both lung and colorectal cancers from 2009 to 2013 among men, Govender points out.

The incidence is the rate at which new cases of a condition in a population increases over a specified period of time, according to the CDC.

“From 2011 the figures show that colorectal cancer incidence has increased in comparison to lung cancers,” Govender explains. “This could be the start of the impact of the obesity epidemic in South Africa.”

Among women in South Africa, Cancer Registry statistics show an increase in reported new cases of breast cancer and colorectal cancer. Govender says this is “possibly resulting” from the growing obesity epidemic.

Linda Bauld, Cancer Research UK’s prevention expert, explains that “extra fat doesn’t just sit there. It sends messages around the body that can cause damage to cells. This damage can build up over time and increase the risk of cancer in the same way that damage from smoking causes cancer.”

But only 15% of people in the UK know that obesity is a cause of cancer, Cancer Research estimates.

A 2015 study in the British Journal of Cancer confirms smoking is still responsible for a huge 54 300 cases of cancer in the UK every year but being overweight or obese causes nearly half as many (22 800 cases or 6.3%). The results suggest that more than 1 in 20 cancer cases would be prevented by maintaining a healthy weight, Cancer Research UK argues.

In South Africa, Govender explains, there is not sufficient research to show the actual percentage of cancers that are lifestyle-related. But, apart from obesity, preventable cancers include those linked to tobacco, alcohol consumption, exposure to the sun and ultraviolet-emitting tanning devices, pollution and lack of physical activity.

“Cancer is not inevitable,” says Govender. “It is possible that many cancers related to overweight and obesity could be prevented.”

Will blunt messaging convince millennials to shake off the kilos or is it fat shaming?

“Fat shaming!” and “Damaging!” — a chorus of protest met Cancer Research UK’s awareness campaign.

Sofie Hagan, a London-based Danish comedian, did not tactfully omit a single letter when she took to Twitter to vent how P_SS_D off she was: “Right, is anyone currently working on getting this piece of shit Cancer Research UK advert removed from everywhere? Is there something I can sign? How the fucking fuck is this okay?”

But Cancer Research says the campaign was never about fat shaming or blaming someone for their cancer.

“It’s not about anybody’s personal eating habits or blaming the individual,” says Malcolm Clark, policy manager for obesity at Cancer Research UK. “Yes, we wanted to raise the fact that there is a link between obesity and cancer, but the aim was to get action across the population to tackle this; to get policymakers and regulators to do more and to show where government should focus its efforts. The purpose was to have a public health campaign.”

The campaign was based on science, Clark emphasises. And although these figures make for grim analysis, they also show that positive changes can decrease the risk of cancer.

In South Africa, Govender says, nongovernmental organisations such as Cansa play a vital role in creating awareness — especially in the absence of a functional and well-resourced national cancer control plan.

But Cansa’s language is considerably more measured. Obesity is a highly stigmatised condition, Govender points out, and even clinicians may use alienating language when they try to talk to patients about their weight.

Adsa’s Jessica Byrne says that, although shock tactics may raise awareness, as has been successfully done in highlighting the dangers of smoking, there is a delicate balance between educating the public about the dangers of obesity and stigmatising or creating a negative body image in those who are overweight.

“Perhaps supportive messages should also focus on the importance of healthy lifestyle choices to prevent cancer, rather than singling out obesity,” she explains.

Cancer Research UK is still awaiting the results of the impact its campaign has had.

There will be considerably more than 15% of people who know about the link between excess weight and cancer, Clark predicts, especially given the level of response, coverage — and outrage.

National Obesity Week 15 to 19 October 2017

In South Africa National Obesity Week follows World Obesity Day on the 11th October. Obesity will continue to increase in South Africa unless changes are made at an individual, familial, community and policy level. The HSFSA also supports government’s efforts to regulate the food industry as one of the strategies to reduce and halt overweight and obesity.

Obesity is defined as a state of having too much body fat, to the extent that it negatively affects health. Whilst obesity has afflicted a small portion of most societies for centuries, only in the last half century has it drastically increased. Obesity is now one of the biggest global health problems of the 21st century. Whilst the prevalence of obesity is levelling off in high-income countries, rates continue to increase in low and middle-income countries, including in South Africa. Half of South Africans aged 15 years and older are categorized as being overweight and 40% of women as obese.

South Africa’s double burden

South Africa is still plagued by undernutrition as high unemployment levels and inflation continues to drive food insecurity. Ironically, undernutrition and overnutrition have become part of the same problem, the one fueling the other. The seemingly opposite conditions are found in the same communities and even within the same households. A low household income results in a monotonous diet based on refined starch, little protein, poor diversity of fruit and vegetables, and salt as the main taste enhancer. With urbanization many traditional vegetables and legumes which provided some good nutrition are readily replaced by cheap processed meat, crisps, deep fried foods, and sugary snacks and drinks. Food choices are mostly driven by price and accessibility. “Bad access to good food and good access to bad food” – says local participants from a report into hidden hunger 1. In one study where researchers compared prices in rural food stores, healthier food choices cost on average 70% more 2. Changes in food consumption patterns confirm that South Africans are eating more kilojoules, more sugary beverages, more processed and packaged food, and fewer vegetables 3.

This poor dietary pattern becomes deficient in many vitamins, minerals and fibre – yet remains sufficient in energy. “In fact, hyperpalatable foods high in added sugar, fat and salt easily provide a surplus of energy. Combined with low activity levels, this is the perfect recipe for obesity” says Gabriel Eksteen, Nutrition Manager at the Heart and Stroke Foundation SA.

Poverty and undernutrition also have an indirect biological impact on obesity. Poor nutrition during pregnancy, infancy or childhood changes metabolism in preparation of a life of food shortages. When a child is subsequently exposed to a surplus energy from a modern diet, obesity and diabetes is more likely than in well-nourished peers. Equally, infants born to obese

mothers are biologically predisposed to becoming obese themselves – with 70% of South African women overweight, the ripple effect can be immense.

Rising middle-class

In South Africa undernutrition also coexists with over-indulgence, further fueling obesity. The rising middle-class who can afford more nutritious food is also unfortunately increasing their portion sizes and adding luxury items high in fat and sugar such as take-outs and sugary drinks. Parents and caregivers who expose their children to a sedentary lifestyle and poor eating habits place them at risk for becoming obese. Childhood obesity is a powerful predictor of adult obesity.

Obesity is weighing down South African progress

South Africa continues to experience urbanization, an increasingly unhealthy modern food supply, and reduced levels of physical activity. Given this trend, obesity is predicted to steadily increase. The World Obesity Forum estimates that nearly 4 million South African school children will be overweight or obese by 2025. The 2016 Global Burden of Disease study reports that although South Africans are gradually living longer, but a greater proportion of life is spent suffering from chronic diseases 4. Unless we act now, the health consequences of obesity will overburden the health care system and decreased productivity will stifle economic progress.

Act now

South Africans need to work together to fight obesity. The Heart and Stroke Foundation SA calls on all role players, including government, the corporate sector, civil society, and the food sector, to act decisively to bring about change. The World Health Organization and the World Obesity Forum both recommend systemic changes to battle obesity. This includes promoting intake of healthy foods and physical activity, preventing obesity pre-emptively during pregnancy and in early childhood, and improving access to weight management services. Environmental changes to improve access to affordable healthy food and opportunities to be physically active is important, whether at school, at work or in communities. Policies to tax unhealthy food and initiatives to subsidize healthier choices are also recommended and cost-effective. Finally, there should be continued pressure on food manufacturers to limit marketing of unhealthy foods and reformulate products.

Professor Pamela Naidoo, CEO of the HSFSA, states that “South Africa is a complex country with glaring inequalities. Obesity, which poses a major risk factor for the onset of many medical conditions, is but one consequence of the inequalities we face. Consequently, the HSFSA is determined to help multi-stakeholder initiatives to reduce obesity and drive advocacy towards this goal.”

References

1) Hidden hunger in South Africa, OXFAM, 2012

2) Temple et al, Nutrition, 2011

3) Ronquest-Ross et al, South African Journal of Science, 2015

4) Global Burden of Disease Study, Lancet, 2017

The Minister of Health has, under section 15 (1) of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act No.54 of 1972), published for public comment the regulations in the

The Minister of Health has, under section 15 (1) of the Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act No.54 of 1972), published for public comment the regulations in the

Lifestyle changes may prevent 4 in 10 cancers

Lifestyle changes may prevent 4 in 10 cancers